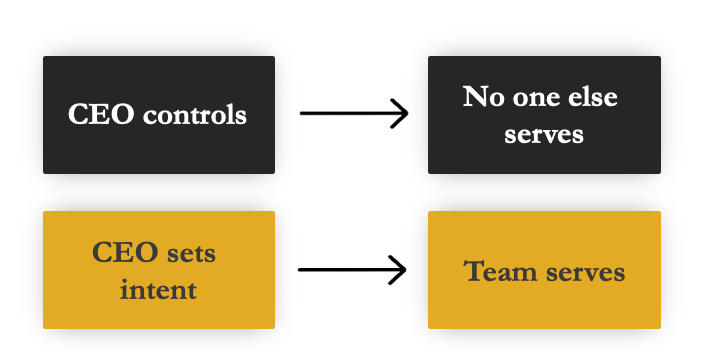

Most CEOs don’t struggle with taking charge. They struggle with letting go.

As I wrote about recently, the majority of CEOs are Dominance types in DISC terms. They are wired to act, decide, push forward. That drive may be what got them the job in the first place. But it can also become a trap.

A dominant CEO might think they are serving their organization by tirelessly working to move things forward. But in reality, they’d often get far better results by stepping back and letting their employees serve the organization.

This is a dynamic found in many areas of life. Straining, pushing, striving for control—it feels like you’re working hard for the outcome you want. But paradoxically, sometimes that outcome is best achieved by stepping back and letting go. (See: Alan Watts’ Backwards Law.)

In the CEO context, this means letting other people take meaningful ownership within the organization. That’s really hard for high-D types. It’s not easy for them to let others do things for them. They fear losing control. They might assume that relying too heavily on others signals weakness.

In reality, it’s the opposite. CEOs who can’t loosen their grip keep everyone else from serving in their own right.

Once you do stop push-push-pushing, you can step back, observe, guide, and make smaller, more strategic, higher-level interventions. Nine times out of ten, you get vastly superior results. It also makes your team a lot happier, because guess what? People want to serve, especially if there’s a worthy mission.

To Let Others Serve, Start with Clear Intent

Letting go only works if you've first clarified your intent as a leader.

Before you can let others serve, you do have to articulate where the organization is going and why it matters. This is a foundational part of the CEO job: to define success in clear terms, paint a compelling picture of the future, and ensure everyone in the organization understands their role in getting there. If you’re a CEO who has trouble letting go, getting that plan in place will help you feel a lot more confident.

(PS: Creating your 1-Page Strategic Plan is a great way to set your intent. You can get started with our new dedicated Ask Joel agent designed to build your Strategic Plan, now in beta. Try it out here. I would love your feedback.)

Too often, CEOs skip this step or blur it with the idea of simply being supportive or accessible. That’s where I see the limits of popular notions like “servant leadership.” While well-intentioned, it places emphasis on support before direction. That gets the sequence of leadership backwards, and it’s part of what can stress D-type CEOs out so much.

Now, Get Out of the Way

Once the vision, strategy, and objectives are clear, the CEO’s role shifts to one of enablement. This is where you must step back and really let your people serve the organization, including the customers, their fellow employees, and even you. That does not mean the CEO must become passive. It means redirecting your energy toward removing obstacles, maintaining focus, and protecting the team from distractions that can pull them off course.

This is where delegation becomes critical and where dominant personalities often hit resistance. Giving up control can feel like giving up excellence. But when you resist delegation, you also resist scale. You stay at the center of every decision, every fire drill, and every inch of progress.

What high-D leaders often miss is that delegation is not about lowering standards. It is about leverage. It is how you multiply your impact through other people.

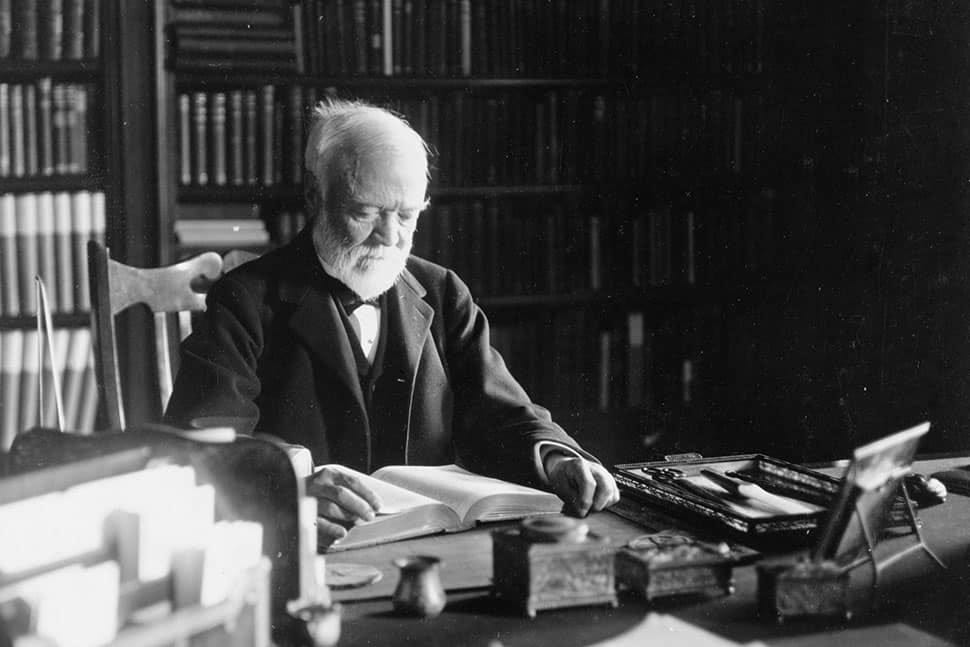

"Here lies a man who knew how to enlist in his service better men than himself." —the self-written epitaph of Andrew Carnegie

Delegation is a muscle, and trust builds over time. Once you work it enough, I think you will be surprised by how much people want to step up and serve with excellence when they are given the space to do so.

This is how great CEOs create energy and momentum across the organization. Not by doing it all themselves, but by creating the conditions where others can lead too.

That is what Andrew Carnegie captured in the note his family found in his desk after he died, intended as his epitaph: "Here lies a man who knew how to enlist in his service better men than himself."

It’s a reminder that the true measure of a CEO’s leadership isn’t in how much they do, but in how much they enable others to achieve.